Silence of the Talking Heads

On close-ups and decapitations

The recent videos showing the decapitations of Nick Berg and others caused vehement reactions not only for their obvious cruelty but also because the very issue of beheading was always regarded as a crucial menace in the clash of cultures and systems. From Salome's demand for the head of St. John the Baptist over the French Revolution's guillotine up to present-day capital punishment in Arabian countries - no matter if for religious, political or social reasons, there is no stricter distinction between humans than the one of those with and those without head.

In connection with film it is difficult not to think of D.W. Griffith's "chopped off heads"[1] and the presumed shock they caused. The reactions to the invention of the close-up became one of the founding myths of cinema. In Life to those Shadows Noël Burch e.g. depicted the anecdote of a shocked woman absconding the cinema with the words "All those severed hands and heads!"[2]. But a reliable source for these stories we get neither from Burch nor other film theorists. In order to understand how recent videos work and what that tell us about the close-up today I have to give a short overview over the history of the close-up.

Primitive vs. Classical

Griffith marks the border between primitive and classical cinema and a crucial landmark of this border is the close-up. Practically all changes from primitive to classical film have to do with the then new media's relief from theatre or to be more precise vaudeville-shows. Griffith of course was not the first to use close-ups. Earlier examples include the films made by the School of Brighton and the famous shooting cowboy from Edwin S. Porter's The Great Train-Robbery (1903) that had a thematic but no narrative connection with the actual story. Griffith integrated these isolated shots in the stream of narration.

The early short films consisted mainly of frontal long shots presented for the audience like a theatre stage. "Moreover, the closeup was not a straight-forward image presenting the actor's face over the whole surface of the frame, chosen from among various other elements, characters, or objects around him. The face was isolated by a circle, the area around which remained black [...] and this result was achieved by photographing the iris enclosing the face - or else through mask. All of which makes it easier for us to understand the meaning of the word closeup, which, as we have seen, refers literally to the framing of the significant detail: 'enclosed and brought forward.'"[3] Mitry's description is misleading to the extent that at that time the face was not a privileged motive of the close-up yet but existed parallel to other objects like hands, letters, keys and signs that needed to be emphasized.

The establishing shot had to be the first and last take of every scene only to be shortly interrupted by closer cut-ins that were seen as details of the long shot image rather than details of the spatial set as the viewer might loose the orientation. From the middle of the teens these restrictions were slowly eased.[4] A scene might start with a closer view and the whole set just later be revealed in a long shot. Hitchcock later pointed out that to start a scene with a medium or even close shot doesn't necessarily have to disorient the viewer but it often makes sense to keep the long shot in reserve for the most dramatic moment.[5]

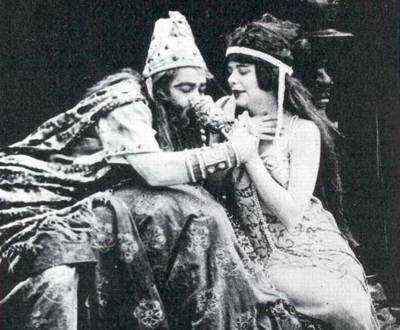

While the highly acclaimed Birth of a Nation (1915) and Intolerance (1916) clearly mark the beginning of classical cinema, the earlier Judith of Bethulia (produced 1913, released 1914) is often regarded as a minor work and a mere product of transition. Toeplitz e.g. just briefly mentions it in his film history as a copy of the Italian history film.[6] With its four reels Judith of Bethulia was the longest American film then and the reason for Griffith's breakup with his production company Biograph after about 400 short films.

Judith of Bethulia

(1913)

Anthony Slide criticizes Judith for it's "stylized acting" and adds that the "battle scenes are badly staged"[7]. But even though the film may sometimes look like a poor precursor for the forthcoming masterpieces it remains interesting as a first effort maybe even because of its shortcomings. "The closeup as we know it was to make its debut as late as 1913, in Judith of Bethulia."[8]

Not without vanity Griffith himself later depicted the situation that his cameraman Billy Blitzer initially refused to shot facial close-ups as the background would be out of focus. Griffith went in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and after finding confirmation in the works of Rembrandt and other classic painters he decided to change the cameraman.[9]

Unity vs. Fragment

The main criterion for a post-primitive close-up is its incorporation in the film through continuity editing. But Griffith's achievement was not alone the unity of the edited film but also the discovery that the privileged subject of the close-up was the human face.

The integration of human faces into what used to be a reproduced stage performance set off a debate among film theorists whether the close-up remains some kind of fragment or produces unity on an even higher level. Rudolf Arnheim e.g. warns that an abundance of close-ups would lead to a disorientation of the viewer[10], while Béla Balázs in contrast emphasizes that the facial close-up has mainly an abstract character. "Because the expression of the face and the meaning of this expression do not have any spatial relation or connection."[11] He opposes the face to other body parts like hands that preserve the reference to their context even when shown in close shots.

"A close-up, which can theoretically show anything, becomes synonymous with the facial close-up, that reveals character. It is significant, however, that extreme facial close-ups - framing closer than full facial shots - are almost absent from the classical cinema, as if cutting the face completely free of the background made the close-up too fragmentary. (Compare the frequency of the enlarged portions of faces in the Soviet cinema of the 1920s.)"[12] Eisenstein criticized Griffith's close-up as a merely quantitative augmentation and demanded that close-ups should not just depict but 'mean'.[13]

In this spirit of abstraction Kuleshov made his famous experiment combining 'uninspired' close-ups of the then famous actor Mozhukhin with unrelated shots of objects and persons. As a result the viewers imagined a connection that never existed. Though truly dialectical in the radicalism of its original version the Kuleshov experiment in the long run had a bigger influence on western than Russian cinema.[14]

The dominance of the face over other subjects when it comes to close-ups leads to Deleuze's definition of what he called the affection-image. "The affection-image is the close-up, and the close-up is the face."[15] The affection-image derives from the tension between the emptiness in the face of a Hitchcockian actor and the celebrated 'micro movements' that in the twenties stood for the superiority of film over theatre.

But when everything shown in a close-up like e.g. a clock face turns into a human face, the human face itself will disintegrate. Maybe therefore Bergman's Persona (1966) marks the end not only of the classical close-up but also of humanistic modernism in general.

So, in the context of montage the close-up can symbolize unifying or fragmentary character of film - both in a positive sense.[16] The menacing character of the close-up itself got more and more neglected in favor of abstraction.

Face vs. Head

"So we see something with our eyes that does not exist in space."[17] The assumption to see something meta-spatial is quite fragile and what happens if we re-imagine what we see in space? The face-image turns back into a head-object. This dialectic between face and head exist parallel the above-described one of unity and fragment.

But when are we talking about faces and when about heads? The term head seems to dominate whenever the close-up appears to be a foreign body within the entity of the film. This obviously applies first of all to the close-ups in primitive cinema. Mitry mentions that close-ups initially were called "big heads".[18] Arnheim in his already mentioned critic of the close-up describes it as an accumulation of heads - not faces. "The close-up shows the human head, but one cannot tell where the man is to whom the head belongs, whether he is indoors or outdoors, and how he is placed in regard to other people - whether close or distant, turning toward them or away from them, in the same room with them or somewhere else. A superabundance of close-ups very easily leads to the spectators having a tiresome sense of uncertainty and dislocation."[19]

The history of the isolated head in cinema can roughly be divided in three phases: the head as an arcane object in primitive cinema, the invisible head of classical cinema and its return in the post-classical cinema since the 70s.

The execution of Mary, Queen of

Scots (1895)

The first head is cut as early as 1895 in Thomas A. Edison's production The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, a 15 second long movie representing the beheading of Queen Mary that in seemingly one long shot includes the first cut and first special effect in the history of cinema. Just when the actress playing the Queen bended down laying her head on the dowel the camera was stopped and the real woman was replaced with a dummy. The cut in the story only becomes possible through a cut in the film - the latter remaining invisible for the audience. As a matter of fact Edison's film picks up a popular topic of contemporary vaudeville-shows that for obvious reasons ended with Mary's head on the dowel and the only falling thing was the curtain.[20] In the following years the head became a catalyst for the development of special effects as in the films of Georges Méliès and others.

Méliès: Un homme de têtes

(1903)

The sculptor's nightmare

(1908)

Toward the end of primitive cinema the function of heads turned from amusement to menace - a premonition of the taboo the head should face in classical cinema. In The sculptor's nightmare (1908) a drunken artist gets arrested and in his delirium dreams of talking busts. The horror is founded in the exchange of the literally animated and dead. A bust is not supposed to move or even talk. Herein lies the crucial difference between the head in traditional arts like portrait painting and the facial close-up: in a motion picture we expect a close-up to be more than a painting but somehow our expectations are always disappointed because it remains passive. This ambivalence is the tension of Deleuze's affection-image, a potential not to be realized. The self-portraits the surrealists made in 1929 with closed eyes resemble simulations of the cinematic close-up with the means of photography because they are addressing a potential that a photo (unlike a close-up) actually does not have.

Sleepy Heads

Judith of Bethulia - a story of beheading as a matter of fact - marks the transformation of the isolated head from fabula to style, from object to image. One might expect that Griffith concealed the head of Holofernes with a close-up of his heroine but it was just the other way around. The audience was accustomed to heads as we have seen but not to close-ups. And when films became longer and multiple lines of actions where introduced this was "explained" by the means of parallel montage as e.g. in Griffith's own Intolerance. Until today we can observe that aesthetic and technical innovations on the level of style or syuzhet are first accompanied by an equal fabula.

Alfred Hitchcock, a loyal heir of Griffith and life-long fascinated of the act of strangling, made with Rear Window (1956) a film about the invisibleness of the head as an object in classical cinema. The film features his maybe most radical MacGuffin - always just refered to indirectly as "it", "in a hat box" or "in the icebox". It is left to the imagination of the viewer what Jeff (James Stewart) and Lisa (Grace Kelly) are looking for. Only in his interview with François Truffaut Hitchcock became more direct: As an inspiration for the film he mentions the case of Patrick Mahon who killed a woman and cut her into pieces. This way he could stash away the complete corpse - but he didn't know what to do with the head? He decided to burn it in his fireplace where due to the heat of the fire the eyes of his victim suddenly opened again.[21]

Since the 70s we can witness parallel to the fading of the classical close-up increasing incidences of separated heads. Starting half comic, half surreal with David Lynch's Eraserhead (1975) as a subculture phenomenon not later than with the shot off bonce of Bobby Peru (Willem Dafoe) in Lynch's own Wild At Heart (1990) decapitation heads for mainstream culture. Peter Greenaway's The Baby of Mâcon (1993) is probably one of the most conscious examples with its references to Christian culture. The story of a virgin birth is staged in a 17th century theatre but the performance becomes "real" and ends with the Christ-like child being cut into pieces and reduced to its head as a Byzantine icon. Greenaway's in every possible way overdeterminated film turns into a short-circuit of painting, theatre and cinema.[22]

The most notorious example within mainstream culture is probably the ending of David Fincher's Se7en (1995) when Detective Mills (Brad Pitt) receives the head of his wife (Gwyneth Paltrow) in a UPS-parcel. Like a amplified echo of Hitchcock's hat box the muted head remains the unspeakable and invisible.

Antro/Socio

Human vs. Post-Human

Since one and a half decade it no longer can be denied that the close-up in cinema and humanism in general are facing a serious crisis. Symptomatic is e.g. Bruce Nauman's video installation Antro/Socio. Initially presented at the documenta in 1992 it shows several close-ups of a bald headed (opera) singer who is continuously singing/shouting "Feed me, help me, anthropology, eat me, hurt me, sociology". As revolving around the own axes the faces turn into heads and the visage into an object.

Meanwhile one of the last realms of identity - the passport-photo - is to be amended with biometric data no longer readable for humans. In the second half of the 19th century passports where abolished in most European countries due to the increased traveling. Only during World War I modern passports including portrait photos were introduced and in 1920 in Paris by the "Conference on Passports and Customs Formalities" internationally standardized. The parallel to film history is obvious. Not by chance Microsoft's "universal login-system" for various internet services is called Passport and as soon as our passports will include biometric data the photo (if not abolished) will be pure decoration.

David Wark Griffith vs. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

To deal with the video Abu Musab al-Zarqawi shown slaughtering an American depicting the beheading of Nick Berg under merely formal aspects might be seen as a pure provocation. But as a matter of fact - beside of its truly barbaric content - it has a form that can be analyzed and put in the context of film history. The video now is distributed freely over the internet and watched not only by Islamic fundamentalists for various reasons. I do not want to discuss the question here if and to which degree the video is a fake. There are in-depth technical analyses available on the internet - all of them dealing with the idea of conspiracy.

I rather want to discuss why the video looks how it looks like and how that relates to the history of moving pictures. The video consists of three parts: a short self-introduction by Berg, a rather long shot of Berg sitting on the floor while five masked man are standing behind him and the actual beheading and presentation of the head. The last part is heavily edited. Beside of the visible cuts there are a lot of dropped or repeated frames as it can be seen by the timecodes from the two cameras used. The video does not contain any close-ups.

The video has various connecting points to Griffith's Judith of Bethulia - most of them of antithetic nature. First of all there is the very subject of decapitation. The setting of Griffith's film is Bethulia, a fictional city somewhere close to Jerusalem that is under the attack of Holofernes and his soldiers. Judith, a Jewish widow, sees only one chance to save her city: to kill Holofernes, who is a general of Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Assyria. Trying to seduce him she falls in love with Holofernes but kills him for the sake of her people.[23] Griffith tells the cruel story not without sympathy for his heroine. When Biograph re-released a 6-reel-version of the film three years later and after Griffith's big successes they gave it the more judging title Her Condened Sin.[24] The taboo of the head showed first effects. The country of Assyria lay along the river Tigris in the area of present-day Iraq. The beheading then and now happened only for psychological reasons. Judith knew that it wasn't enough to kill Holofernes in order to save her city from his army. The soldiers had to be demoralized by the public presentation of Holofernes' head. The connection between a Jewish woman beheading and Assyrian soldier and Islamic terrorists killing a Jewish American is quite obvious. The man in the video who identifies himself as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi defends the decapitation as a reaction to abuses of Iraqi prisoners by Americans in the Abu Ghraib prison.

The Berg-video does not contain close-ups but it even can be said that it doesn't show faces either. In his definition of the affection-image Deleuze stated that not only every close-up is a face but also that every face is a close-up even if not filmed that way. In the introduction part of the video Berg is first shown slightly from the side before there is a cut to the second frontal camera. Both shots are medium shots with similar cadrage. Maybe there just was a problem at the beginning of the frontal take but the effect of the two shots is clearly that he is presented as an object. The second shot looks like a correcting in order to avoid a spatial presentation of the room as it is. Berg's face remains frozen maybe because of narcotics or the stress of the situation. The five man in the following long shot(s) are all masked and therefore without faces. It was noticed that even during the beheading Berg seems not to react and might already have been dead. The origin of the screams is unclear too.

Even during the beheading with its chaotic editing the spatial situation remains frontal like in primitive cinema. The action is staged in a way that reminds very much of the theatrical origins of cinema. As there are no faces there is no mimic and actions have to be shown in the so called "pantomime style" of early cinema: the cutting itself and especially the presentation of the head. From a western perspective the video proves to be "primitive" in any way but it makes clear that the menace of the isolated face/head is not based on its decontextualisation as Arnheim e.g. thought but rather on its lack of expression. The stories of Judith and Salome were respected not to say popular topics in art history but disappeared with the close-up of classical cinema because a motion picture could not contain a motionless human face.

Documentary vs. Fiction

Another unsettling fact about the video is that it blurs the border between real and staged. On the one hand we have to assume that we see how a man is killed and as we saw him alive at the beginning and have no reason to doubt that he is dead now it does not matter if we see the "real" killing or if Berg was already dead when his head was cut. On the other hand we have no chance to see the video as a documentation of something that is supposed to happen independently from it as we would demand it from a documentary. Everything is staged for the camera but not fictional.

The often-cited opposition between fiction and documentation represented by Georges Méliès and the Lumières can be regarded as another myth of cinema as we know by now. But to play consciously with the non-existence of this border was especially in the first half of the the 90s a re-occuring theme of independent cinema in films like C'est arrivé près de chez vous/Man Bites Dog (1992), Zusje/Little Sister (1995) and the already mentioned The Baby of Mâcon.

Kristin Thompson has pointed out that the turn from mainly documentaries to narratives in the years 1906-7 was caused by the demand to deliver an increasing number of films in a predictable way to nickelodeons and vaudeville theatres.[25] As the Berg-video is only one out of several beheading-films and taking into account the mode of production it cannot be seen merely as an attack on the western culture industry as defined by Adorno and Horkheimer. Though the results look still primitive, terrorists take on professional modes of production in order to fight in the war of images.

Saddam Hussein after being

arrested

After the arrest of Saddam Hussein the main interest was to proof his identity and to present him in a close-up on TV. From a western perspective this might seem "natural" but it stands in a strict contrast with the decapitation videos on the other side. It is difficult to understand for us why a man claims to be Abu Musab al-Zarqawi masks himself at the same time though we have photos of him. Hussein's newly grewn full beard in this context seems like a clumsy self-protection against his medial beheading.

The decapitation videos are "working" as we have seen not only because of their content but also because of their very form. They are full of references that not only make them comprehensible but unsettling at the same time. As the timecodes in the Berg-video tell us there are two cameras but there is no shot-reverse-shot-editing, there is no parallel montage, there is no relief. It's like hopping from one channel to the other and finding the same program everywhere. Cutted heads presented in the style of early cinema are supposed to be funny but these are not.

Birk Weiberg

07/2004

[1] Béla Balázs, Der Film, Globus-Verlag, Wien 1949, p.

61 > back

[2] quoted after Jan Speckenbach, Die Großaufnahme. Ikone oder

Maske?, unpublished master thesis, Karlsruhe 1998, p.

42. > back

[3] Jean Mitry, The Aesthetics and Psychology of Cinema,

Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis 1997, p.

70 > back

[4] compare David Bordwell/Janet Staiger/Kristin Thompson, The

Classical Hollywood Cinema. Film Style & Mode od Production to

1960, Routledge, London 1988, p. 197 > back

[5] François Truffaut, Mr. Hitchock, wie haben Sie das

gemacht?, Munich 1984, p. 215 > back

[6] Jerzy Toeplitz, Geschichte des Films, Vol. 1, 1895-1928,

Henschelverlag, Berlin 1972, p. 86 > back

[7] Anthony Slide, Early American Cinema, The Scarecrow

Press, Inc. Metuchen, N.J. & London 1994, p.

99f > back

[8] Mitry, p. 70 >

back

[9] The Man Who Invented Hollywood. The Autobiography of D.W.

Griffith, edited and annotated by James Hart, Touchstone

Publishing Company, Louisville, Kentucky 1972, p.

85f. >

back

[10] Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art, Faber and Faber, London

1983, p. 74 >

back

[11] Balázs, p. 61 > back

[12] Bordwell, p. 54 > back

[13] S.M. Eisenstein, Dickens, Griffith and Ourselves, in:

Selected Works, Vol. III, Writings 1934-47, ed. by Richard

Tayler, BFI, London 1996 > back

[14] Hithcock as a main adaptor of Kuleshov's concept refers to

him in his interview with Truffaut. p. 211 > back

[15] Deleuze, p. 123 > back

[16] Speckenbach gives an excelent overview over the contrary

position of Mitry and Bonitzer about this question. p.

12ff >

back

[17] Balázs, p. 62 > back

[18] Mitry, p. 69 >

back

[19] Arnheim, p. 74 > back

[20]

http://www.editorsguild.com/newsletter/SepOct03/sepoct03_first_cut.html > back

[21] Truffaut, p. 217 > back

[22] When around 1914 several production companies tried to

strengthen the bonds between theatre and film - by adapting plays

and working with famous stage actors - Griffith declared clearly

that theatre and film had nothing in common. compare Toeplitz, p.

87 > back

[23] The love story was Griffith's change compared to the

original theatre version. comp. Edward Wagenknecht, The Movies

in the Age of Innocence, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman

1962, p. 65 >

back

[24] Wagenknecht, p. 65 > back

[25] Thompson, p. 115f > back